Things Left Unsaid

Things Left Unsaid

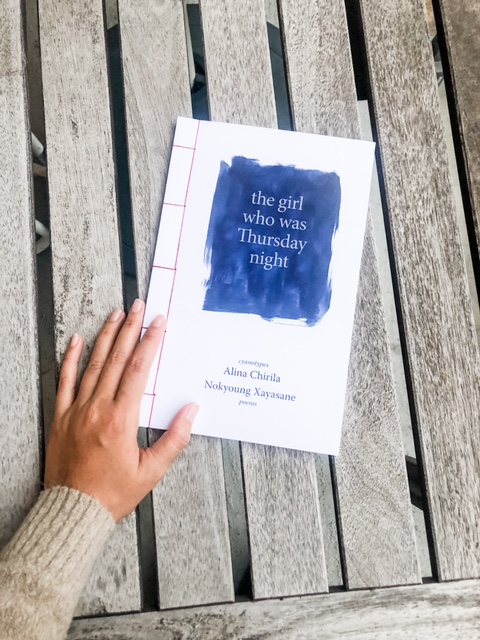

Nokyoung Xayasane

If she were honest with herself, it hadn’t turned out how she hoped it would. Her expectations had gotten the better of her.

Sam stood leaning against the kitchen counter. She had thrown the pregnancy test into the trash before Eric got home from class. There had been a part of her that had hoped the test would be positive and another part of her, a larger more looming part, that prayed the opposite. She was no longer a religious person but praying seemed to be the best route. Please, she had prayed. I’m not ready. Maybe someday but not today.

If the test had been positive she knows her mom would be happy. Mai would be a grandmother like many of her friends whose kids hadn’t kept going on and on with more and more schooling. What’s with all the schooling, she’d say. What is it you’re learning exactly?

The owl eyes of her teapot and cups stared back at her. The sink was empty of dishes but she had to get used to not having a dishwasher. Washing the dishes was like taking a shower—her thoughts wandered and vaulted here and there as the soap suds dispersed. Shower thoughts. Dishwashing thoughts.

“Everything good?” Eric asked her while he held the refrigerator door open, scanning the contents for an after-class snack. Sam was still slightly amazed and annoyed at how quickly Eric had lost weight ever since he decided to cut out beer and processed meat from his diet. He shed the pounds like it was nothing. A preening heron on the edge of the water, regal and distant.

He had come from a divorced home where his mom, an eccentric novelist, filled his plates with her latest concoctions of gluten-free, cauliflower-crust pizzas and meatless nuggets. He seemed to have gained weight in an act of rebellion. But now that he wasn’t under her iron apron, rebelling through food wasn’t as high a priority.

Eric had lived with his mom and his aunt Celeste, a professional volunteer. She hadn’t been paid for any of her work, but she loved giving of her time as a museum guide or food tour guide. She also volunteered at the homeless shelter. Sam refrained from correcting her and saying “unhoused.” It was around the time of Eleanor’s first swipe at a novel that she adopted a cat and named him Kevin. Subsequently, John, Alfred, and Pam followed. Sam found the human names endearing, but still got confused when Eleanor would talk about Pam’s latest poop or Kevin’s finicky eating habits. They were Eric’s siblings. Round, rotund, purring.

“Yeah, I’m good. How was class?”

“Like every other day. I hardly talk to anyone. It feels like I only use my voice when I get home.”

The thing that had drawn Sam to Eric was their conversations. He would play devil’s advocate and it would get her all worked up. How could he defend bestiality? Easily. He spoke in a reasonable tone, hardly ever raised his voice, and listened, really listened. He never reacted. It was a dance, a collaboration of thoughts and ideas. She fell in love, not with his ideas, but how he presented them. She could put their conversations on mute and just watch his hands and face, extrapolating, reaching, and then finding solid ground. To not be able to do that everyday must really bother him.

“You haven’t made any friends?”

“No, not really.”

Eric was the kind of person who made his friends in grade school and just stuck with those same people. Ever since they had moved to Toronto, he would visit them as often as he could over the weekends. It was as if his real life were back with them and this life with her was a interlude until he could be with them again.

“Speaking of chatting: I had coffee with Padma today.”

“Oh, nice. How’s she doing?”

“She’s good. She talks a mile a minute. She seems like she has all these thoughts rolling around in her head and she needs to get them out as soon as possible. I find her kind of intimidating. I feel like I need to take a nap to recover.”

Eric smiled.

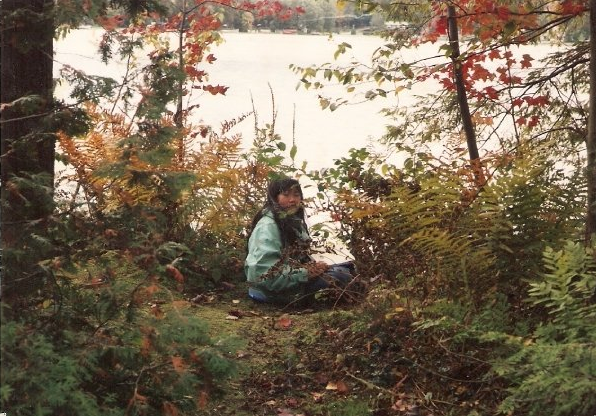

Padma lived close to them on St Clair and Bathurst. Eric and Sam had chosen St Clair and Dufferin because his friend from Kitchener had moved to Toronto before them and lived close by. His friends were still a signpost for him even in apartment hunting. Padma was also from Kitchener, a university friend of Sam’s. Someone highly intelligent and heavily involved in politics and the social sphere. If there was a left-leaning protest, Padma was there. Sam found her passion energizing and then eventually exhausting. Sam preferred quiet activities like poetry readings and conversations in dimly lit rooms. She was a writer herself. A poet. Not something most people would understand given all the science courses she had taken throughout her schooling. But words drew her in. If there was a stanza that rang true and painful, she was there. It was a door opening. She held her breath and walked through.

“I was wondering. You wouldn’t mind if I had a chat with her, would you?”

Eric had been thinking lately about going to law school even though he was currently enrolled in lab tech courses at York University. That was also a reason why they lived at Dufferin and St Clair.

“No, of course not. I think she’ll be able to answer a lot of your questions. Give you a better idea of what being a lawyer’s actually like.”

Padma’s career as a criminal defense lawyer kept her busy. In all seriousness, Sam couldn’t see Eric as a lawyer. He was more of a collaborator, artistic. From what Padma had said about her work, it seemed like it was every lawyer for themselves.

“Yeah, I think so, too.” He paused. “You sure you’re okay?”

Sam smiled. “Yeah, just tired.”

“Right. You need a nap to recover.”

“The introvert’s life.”

For some reason, years later Sam remembers how she talked about Padma that day. She had said Padma had intimidated her. In her eyes, it made her sound weak and fragile. In a position of disadvantage, in a state of admiration, almost. She wonders how Eric remembers it. Perhaps he took note of it silently, unconsciously. Perhaps it allowed them to stand beside each other and be compared without his knowledge or theirs.

There was a time, Sam thinks, when they were happy. It wasn’t as if they were unhappy—just kind of settled, in a certain routine. Eric got bored easily which may explain why they had moved three times in the last three years, almost every year, and for some reason, usually during the winter months, the worst time to move. But he always had help from his friends and bandmates. Being in a band was as if you belonged to a club whose members belonged to a larger club of other musicians. It was kind of like the nod that bikers give each other as they ride by or runners who raise their hand in greeting to another runner in passing.

“I don’t really think about it,” Eric said. Sam tries to remember what she had asked him. It was something along the lines of, “Do you ever think about tomorrow?” Or something less flowery and more pragmatic.

“I don’t really think about it.”

“Maybe that’s the problem.” She had said this softly and in a non-accusing tone. She had never brought up the pregnancy test to him. Eric, who never really thought about tomorrow. Except when it came to potentially becoming a lawyer? Perhaps that was only a glitch that can be seen from a distance when time has passed. A character oversight that only makes sense later on.

Eric had been the first to move out. He had found a place quickly and with two friends she had never heard of before. She was staying until the end of their lease. Two weeks in the empty apartment and then she was moving uptown to Yonge and Eglinton with her university friend Candace.

But until he had found a place, they lived together for two weeks after deciding to end it. Sam was in a state of mourning and they were both in denial. They acted as if nothing had happened. They were bidding their time and wanted to staunch the wound before it bled out. And the best way to do that was to pretend like they were still together. At first they had tried not touching each other, even in passing between the kitchen and living room, but that seemed strange. They made a decision to act normal, whatever that meant. It was a form of self-preservation. A form of self-inflicted insanity.

They went to the movies together. It was an outdoor film festival at Christie Pits. Sam looked at the screen. Moving figures and ricocheting sounds bouncing off the nearby houses and buildings. A dark world lit up by one small screen. Lives were unfolding with cinematic precision, one cut moving on to the next, self-assured and self-propelling. The score rising and falling, now hushed, barely a whisper, hardly a sound. She looked around her and saw the blue light of the film reflecting off people’s faces. Eric looked up and away, mesmerized. She reached her hand out and grabbed onto nothing, just empty air.